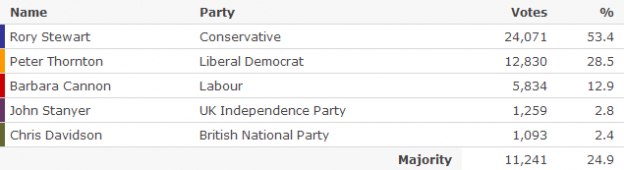

Article first published in The Times on 5 May 2010.

Talking newts and quoting T. S. Eliot in a rural tearoom stands a dangerous young man. Cynics will encounter Rory Stewart, 37, at their peril: he might just begin to restore their faith in politicians.

The Oxford-educated Old Etonian and bestselling author has been a soldier, diplomat, deputy governor of an Iraqi province, head of an Afghan charity and Harvard professor of human rights. He has trekked 6,000 miles across Iran, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan and India. He is charismatic, highly intelligent, an independent thinker and a friend of presidents and royalty.

Yet Mr Stewart is about to take on the unglamorous compromises of life on the Tory benches at a time when the reputation of MPs lies shredded.

Mr Stewart, with his mop of dark hair and angular frame, is unfailingly polite and engaging. He puts people at ease, is interested in their concerns and opinions, asks questions and makes notes. Prompted, he shares his thoughts on everything from bus shelters to the global economic crisis.

He does not curry easy favour, rejecting one woman’s sweeping condemnation of the European Union and arguing — gently — against an elderly man’s yearning for “stringing up murderers without trial”.

We are in Longtown, spectacular hill country near the Scottish Border. The campaign soundbites, media events, TV debates and Rochdale blunders belong to another world. In this constituency, three quarters of the people live in villages of fewer than 300 people, and there are 3,700 farms. The 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease was devastating. Agriculture has barely figured in the national campaign.

Mr Stewart had answered David Cameron’s call for candidates with no background in party politics because, though uncomfortable with the phrase “Big Society”, he is, he said, “an apostle” for what it means: “It’s accepting the wisdom of the local, giving more financial power and discretion and freedom to communities at a parish and town level. It’s about trusting people like head teachers and letting them get on with it.

“Labour has done a lot of good things but my experience of working with the Government over the years I was in Afghanistan was frustrating because I came up against an instinctively centralising, regulatory mindset that wasn’t comfortable with trusting the people on the ground.”

Mr Stewart has done a 400-mile tour on foot of the constituency — every parish — and has been invited into strangers’ homes for a meal and a bed overnight. He is at his happiest out walking and is “a bit apprehensive” about what it might be like in Parliament.

“There are parts of the party’s manifesto I disagree with, but I can’t always be a maverick and say whatever I like on any given subject. There are times when you need to compromise.”

He would oppose party policy only on something “fundamentally against the interests of your constituents or if there was something that went fundamentally against your conscience”.

Westminster was worth the drawbacks because “if you’re really interested in tackling over-regulation and giving power back to communities, you can only do that through politics”.

One voter spoke of being ordered by officials to erect special fencing to protect a habitat for great crested newts. It cost £10,000 per newt. Perhaps the Commons should have special fencing for rare species such as Mr Stewart.