UNDAUNTED

Article first published in the September 2007 edition of Smithsonian Magazine by Joshua Hammer.

In the mud and dust of late-winter Kabul, Rory Stewart leads me through a seedy bazaar along the north bank of the Kabul River. I follow as the British adventurer turned historic preservationist ducks beneath an archway that connects two sagging, earthen-walled houses. Instantly, we’ve entered the narrow passages of a once-grand neighborhood, constructed in the early 1700s by an Afghan warlord, Murad Khan, and his Iranian-Shia foot soldiers, the Kizilbash. Today, the area—known as Murad Khane—shows the devastation wrought by decades of war and neglect. For the past ten months, Stewart and an international team of architects and engineers, working in concert with a number of Afghans, have been trying to resurrect—house by house—this moribund heart of their capital.

At the edge of a field littered with half-collapsed, mud-walled homes, Stewart gets down on all fours and guides me into a crawl space between the foundation and ground floor of a traditional earthen-walled, timber-framed Afghan villa he calls Peacock House; to protect it from floods, they have raised the villa some three feet above its stone foundation with wooden blocks. “This building was ready to collapse when we got here,” Stewart tells me, lying flat on his back. “The stone was crumbling, most of the beams were either missing or rotting. We were worried the whole thing would cave in, but we’ve succeeded in stabilizing it.”

Stewart and I wriggle out from under the building, slap dirt off our clothing and climb a muddy ramp that used to be a flight of stairs. The second floor, once the main reception room of this wealthy merchant’s home, reveals faint traces of its former glory. Stewart gestures to elegant, Mogul-style niches carved into a back wall: “We’ve been scraping gently; this is all recently exposed,” he says, running his hand over a richly detailed latticework screen that has been minutely reconstructed. Then his eye catches something that makes him grimace: a piece of plasterwork over a doorway, newly embellished with a curlicue painted bright orange. “I object to this completely,” he says. “You don’t need to restore every missing piece. You have to accept there are certain bits missing.”

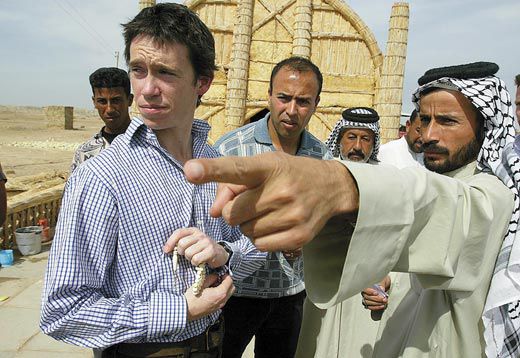

Architectural preservation is not a subject in which Stewart would have claimed expertise as recently as a year ago. But the 34-year-old diplomat and author is a quick study, who in the dozen years since his graduation from Oxford University, has embarked on a succession of extraordinary enterprises. He walked 600 miles across rural Afghanistan in the wake of the Taliban’s fall, most of it alone, and described the experience in The Places in Between, a best-selling work of travel literature. He served as deputy governor of Maysan Province in southern Iraq after the U.S.-led invasion, where he settled tribal feuds and attempted to curb the rising power of Shia extremists. (That produced a second widely acclaimed book, The Prince of the Marshes, written while Stewart was a fellow at Harvard in 2004-5.)

In 2006, Stewart shifted from nation building to development. With his book royalties and seed money from the Prince of Wales, a longtime friend and mentor, Stewart founded the Turquoise Mountain Foundation in Kabul. Located in a renovated fortress on the decrepit outskirts of the city, the foundation (named after an Afghan capital destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1222) has established workshops for the revival of traditional Afghan crafts—calligraphy, woodworking and pottery. Most ambitiously, Turquoise Mountain has begun to transform the face of Kabul’s ruined Old City. Workers have shoveled thousands of tons of garbage from the quarter’s fetid streets and dug sewers and drainage ditches; architects have inspected the 60 buildings still standing, designated 20 as architecturally significant and begun to restore a handful. Stewart envisions a riverside commercial hub in the city center, clustered around a school for the arts that showcases traditional Afghan building techniques.

The project is by no means assured of success, as a glance around the quarter—a monochromatic wasteland of sagging houses and vacant lots—attests. Stewart is up against severe weather, bureaucratic inertia and the opposition of local developers who want to raze what’s left of Murad Khane and erect concrete high rises. (In fact, the Afghan government had earmarked the entire neighborhood for demolition until Afghan president Hamid Karzai intervened last year.) There’s also the difficulty of accomplishing much of anything in a country that remains one of the poorest and most unstable in the world. A resurgence of fighting beginning in early 2006 has unsettled much of the country and killed more than 3,000. Several suicide bombers have struck in Kabul during the past year. “Many people won’t give me money to invest in Afghanistan, because they believe the Taliban are going to sweep back in,” Stewart says. “I don’t believe that’s going to happen.”

When Stewart is not overseeing his foundation, he is on the road—a recent trip included stops in Washington, D.C., London, Kuwait, Dubai and Bahrain—wooing skeptics. At a time when many international lenders are scaling down support of Afghan-related projects, Stewart has raised several million dollars, enough to sustain the foundation and its projects at least through the end of this year; he hopes to raise funding for three additional years. “People like to criticize Rory for having these grand visions,” says Jemima Montagu, a former curator at the Tate Gallery in London, who arrived in Kabul last winter to help Stewart run the foundation. “But of all those I know who talk grand, he delivers.”

One bright morning this past March, I took a taxi to the headquarters of Turquoise Mountain, located in a southwest Kabul neighborhood, Kartai Parwan. The barren hills that surround the city were dusted with snow and ice; the Hindu Kush range, 20 miles north, dazzled white over a mud-brown landscape. As dust from construction sites mingled with car exhaust, the taxi bounced through cratered streets, past pools of stagnant water. At every intersection, the vehicle was set upon by blind and crippled beggars; thin young men selling mobile-phone cards; and ragged boys armed with dirty cloths.

Before long, I arrived at what could have been a wayside inn on the ancient Silk Road, complete with a cedarwood watchman’s kiosk, now purely decorative, with finely wrought panels and latticework screens. I passed through a security check at the gate, crossed a dirt courtyard and entered a small stucco administration wing, where Stewart sat behind a desk in his office beneath a window framing one of the best views in Kabul. He looked a bit bleary-eyed; as it turned out, he had been up most of the night completing his second article of the week—on the futility of using military force to pacify violent Pashtun areas of Afghanistan—as a guest columnist for the New York Times.

The foundation, which sprawls across several walled-off acres, is dominated by the qal’a, a towered mud-wall fortress built by a royal Tajik family in the 1880s. Turquoise Mountain leased the structure from an Afghan widow last year and has since reconstructed two of its ruined portions, landscaped the interior garden and turned the surrounding rooms into art galleries and living quarters for an expanding staff—now up to 200.

On this morning, Stewart exchanged pleasantries in near-fluent Dari (the Afghan dialect of Farsi, or Persian) with gardeners in the grassy terraces behind the qal’a, and soothed a receptionist distressed by the commandeering of her computer by a colleague. He led me into the ceramics workshop, a dark, musty room permeated with the odors of sweat and moist clay. There, the ustad, or master, Abdul Manan—a bearded ethnic Tajik that Stewart recruited from Istalif, a town in the foothills of the Hindu Kush famed for its artisans—was fashioning a delicate, long-necked vase on a pottery wheel.

In a classroom across the grounds, Stewart introduced me to Ustad Tamim, a renowned Afghan miniaturist and graduate of the Kabul School of Fine Arts who had been arrested by Taliban thugs in 1997 for violating Koranic injunctions against portrayals of the human form. “They saw me on the street with these pieces, and they knocked me off the bicycle and beat me with cables, on my legs and my back, and whipped me,” he told me. Tamin fled to Pakistan, where he taught painting in a refugee camp in Peshawar, returning to Kabul shortly after the Taliban were defeated. “It’s good to be working again,” he says, “doing the things I am trained to do.”

As he retraces his steps back toward his office to prepare for a meeting with NATO commanders, Stewart says that “the paradox of Afghanistan is that the war has caused the most unbelievable suffering and destruction, but at the same time, it’s not a depressing place. Most of my staff have suffered great tragedy—the cook’s father was killed in front of him; the ceramics teacher’s wife and children shot dead in front of him—but they are not traumatized or passive, but resilient, clever, tricky, funny.”

A taste for exotic adventure runs in Stewart’s DNA. His father, Brian, grew up in a family based in Calcutta, fought in Normandy after D-Day, served in the British colonial service in Malaya throughout the Communist insurgency there, traveled across China before the revolution and joined the Foreign Office in 1957. In 1965, he met his future wife, Sally, in Kuala Lumpur. Rory was born in Hong Kong, where his father was posted, in 1973. “The family traveled all over Asia,” Sally told me by phone from Fiji, where she and Brian reside for part of each year. At Oxford in the 1990s, Rory studied history, philosophy and politics.

After university, Stewart followed his father into the Foreign Office, which posted him to Indonesia. He arrived in Jakarta in 1997, just as the country’s economy was imploding and riots eventually forced the dictator, Suharto, to step down. Stewart’s analyses of the crisis helped to earn him an appointment, at 26, as chief British representative in tiny Montenegro, in the Balkans, where he arrived just after the outbreak of war in neighboring Kosovo. After a year in Montenegro, Stewart set out on an adventure he had been dreaming of for years: a solo walk across Central Asia. “I had already traveled a lot on foot—across [the Indonesian province of] Irian Jaya Barat, across Pakistan—and those journeys stayed in my memory,” he says.

In Iran, Stewart was detained and expelled by Revolutionary Guards after they intercepted an e-mail describing political conversations he had with villagers. In Nepal, he came close to giving up after trekking for months across Maoist-occupied Himalayan valleys without encountering another foreigner or speaking English. Near the halfway point, agitated villagers in Nepal approached him, saying something about “a plane,” “a bomb,” “America.” Only when he reached the market town of Pokhara four weeks later did he learn that terrorists had destroyed the World Trade Center—and that the United States was at war in Afghanistan.

Still trekking, Stewart arrived in that country in December 2001, just a month after the Northern Alliance, backed by U.S. Special Forces, had driven the Taliban from power. Accompanied by a huge mastiff he named Babur, Stewart walked from Herat, the ancient bazaar city in the northwest, across the snowy passes of the Hindu Kush, ending up in Kabul a month later. The Places in Between, Stewart’s account of that often dangerous odyssey, and of the people he met along the way—villagers who had survived Taliban massacres; tribal chieftains; Afghan security forces; anti-Western Pashtuns—was published in the United Kingdom in 2004. Despite its success there, American publishers did not pick up the book until 2005. It got the lead review in the Sunday New York Times Book Review, was on the Times’ best-seller list for 26 weeks and was listed by the paper as one of the year’s five best nonfiction books.

Stewart applauded the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq; in his travels across Iran and Afghanistan, Stewart says, he had seen the dangers posed by totalitarian regimes and believed ousting Saddam Hussein would, if managed properly, improve both the lives of Iraqis and relations between the West and the Islamic world. In 2003, he volunteered his services to the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and, when his letters went unanswered, flew to Baghdad, where he took a taxi to the Republican Palace and knocked on the door of Andrew Bearpark, the senior British representative in the CPA, who promptly gave him an assignment. “I had a raft of people asking for jobs, but everybody was asking via e-mails,” recalls Bearpark. “He was the only person who had the balls to actually make it to Baghdad.”

Bearpark dispatched Stewart to Maysan Province, a predominantly Shia region that included the marshes Saddam had drained after the 1991 Shia uprising. Setting up an office in Al Amara, the capital, Stewart found himself caught between radical Shias who violently opposed the occupation, and hungry, jobless Iraqis who demanded immediate improvements in their lives. Stewart says that he and his team identified and empowered local leaders, put together a police force, successfully negotiated for the release of a British hostage seized by Moqtada Al Sadr’s Mahdi Army and fended off attacks on the CPA compound. “I had ten million dollars a month to spend, delivered in vacuum-sealed packets,” he recalls. “We refurbished 230 schools, built hospitals, launched job schemes for thousands of people.” But their work was little appreciated and, all too often, quickly destroyed. “We’d put up a power line, they’d tear it down, melt the copper and sell it for $20,000 to Iran. It would cost us $12 million to replace it.” He says only two projects in Al Amara engaged the Iraqis: a restoration of the souk, or market, and a carpentry school that trained hundreds of young Iraqis. Both, Stewart says, “were concrete—people could see the results.”

As the Mahdi Army gathered strength and security deteriorated, the CPA turned over power to the Iraqis, and Stewart returned to Afghanistan. He arrived in Kabul in November 2005 determined to get involved in architectural preservation, a cause inspired in part by his walk four years earlier. “I saw so much destruction, so many traditional houses replaced by faceless boxes. I realized how powerful and intricate [Afghan tribal] communities can be and how many potential resources there are.” A promise of financial support came from the Prince of Wales, whom Stewart had met at a dinner at Eton College during Stewart’s senior year there. (At 18, Stewart tutored Princes William and Harry at the royal estates in Gloucestershire and Scotland.) Prince Charles arranged an introduction to Afghan president Hamid Karzai. Stewart also met Jolyon Leslie, who directs the Historic Cities program for the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, a foundation that promotes urban conservation in the Muslim world. The trust, which has restored major sites in the Old City of Kabul, is preparing to begin work in a residential gozar, or neighborhood, of 254 buildings. “We sat down with an aerial photograph of Kabul and batted around ideas,” Leslie recalls.

Eventually Stewart set his sights on Murad Khane, attracted by its mixed Shia-Sunni population, proximity to the river and scores of buildings that Leslie and other experts deemed worth saving. With Karzai’s support, Stewart lined up key government ministers and municipal officials. The biggest breakthrough came in July 2006, when several Murad Khane landlords—some of whom had been initially skeptical—signed agreements granting Turquoise Mountain five-year leases to renovate their properties.

A few days after my first meeting with Stewart, we travel by Toyota Land Cruiser through the muddy alleys of central Kabul, bound for another inspection tour of Murad Khane. Near the central bazaar, we park and walk. Stewart threads his way around carts piled with everything from oranges and Bic pens to pirated DVDs and beads of lapis lazuli, conversing in Dari with turbaned, bearded merchants, many of whom seem to know him—and he them. “That fellow’s cousin was shot twice in the chest and killed in front of his stall last week,” he tells me, just beyond earshot of one acquaintance. “It was an honor killing.”

It is hard to imagine that anyone—even the fiercely ambitious Stewart—can transform this anarchic, crumbling corner of the city into a place appealing to tourists. “It’s not going to look like Disneyland,” he admits, but “you will have houses renovated. You will have sewers, so the place won’t smell, so you won’t be knee-deep in mud. The roads will be paved; 100 shops will be improved; a school of traditional arts will be based here with 200 students.” It is possible, he acknowledges, that the project could fizzle out, done in by government indifference and a drying up of funds. Stewart predicts, however, that this will not be the case. “It was fashionable five years ago for people to say ‘everybody in Afghanistan is suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome,’” he says, referring to the recent Taliban past. “That is simply not true.” Turquoise Mountain’s team, Afghan and expatriate alike, he believes, ultimately may well rejuvenate a historic neighborhood—and restore a measure of hope to an impoverished, fragile city.