OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS INTERVIEW

Interview first published on harcourtbooks.com in 2006.

Interview first published on harcourtbooks.com in 2006.

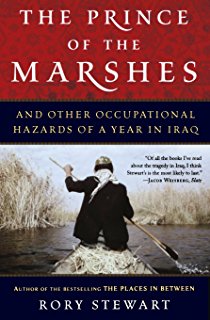

Rory Stewart has covered a lot of ground—figuratively and literally. He spent sixteen months on his feet traversing Iran, Pakistan, India, and Nepal. He then embarked on the second stage of his walking tour: crossing Afghanistan from Herāt to Kabul. The Places in Between captures his experiences on that epic journey. After a brief rest in his native Scotland, he returned to Iraq as a diplomat working for the Coalition Provisional Authority. The Prince of the Marshes recounts Stewart’s eleven months as the appointed deputy governor of, two impoverished marsh regions of southern Iraq. The Prince of the Marshes reveals the difficulties, frustrations, and hazards Stewart faced as part of the Coalition trying to establish a new Iraqi nation.

Q: What made you volunteer for service in the Coalition government in Iraq? What in your background prepared you for this position?

A: I had served in the foreign service in Indonesia, Yugoslavia, and Afghanistan. I had, therefore, been close to a number of “foreign interventions,” and I had direct experience in post-conflict reconstruction. In every case there were problems—foreign coalitions are often incompetent and ineffective—but in every case I found the local population was pleased that the previous regime had been removed, and felt better off after the intervention than before it. I hoped the same would be true in Iraq. I was also interested in rural areas such as Maysan, particularly after spending twenty-one months walking through remote Asian villages.

Q: What did you see as your duties as deputy governor, and how did you set about effecting them?

A: My primary duty was to form an effective and humane government, able to represent the people, keep security, and deliver services. My colleagues and I met eight or nine hours a day with tribal sheikhs, religious leaders, businessmen, and union leaders, trying to answer grievances, win support, and deter our opponents from rioting or attacking our building. We also spent months rebuilding half the schools and all the clinics and hospitals in the province and setting up mass employment schemes.

As the situation became more difficult, I focused on implementing quick, visible construction projects to prove that the Coalition was doing something constructive. Finally, when the insurgents had captured much of the province, my ambitions became more limited: I aimed to set a personal example, to demonstrate that we were at least working hard and in good faith. That decline in ambition represented the increasing desperation of our administration—our dreams of creating a new political culture were reduced to spending money, and, finally, to acting out a symbolic role, with very little power to achieve change.

Q: How did the situations in which you found yourself compare to your previous experiences in the foreign service, and to what you had expected to find in Iraq?

A: Foreign service officers—and I was no exception—tend to spend their time in embassy compounds, negotiating with other diplomats. We have little training in the bold executive decisions required to manage a semi-war zone. I found myself drawing much more on my experience of walking Asia on foot, having to negotiate my way across remote Islamic countries and win the confidence of the five hundred villagers with whom I stayed.

I expected Iraq to be more like Afghanistan, where I could walk relatively securely in the streets and where many people seemed welcoming. I particularly expected this in the south, where the Shia Marsh Arabs had suffered badly under Saddam. Many of the people I worked with had been tortured, and almost everyone had a close relative who had been killed by the security service. So I was shocked to encounter immediate hostility in the streets, with young men spitting as I passed; it made me wonder what had gone wrong. But even so, it took me a while to realize how serious this instinctive antipathy—part nationalist, part religious—was going to be for the occupation.

Q: Initially you supported the war in Iraq. Why? What made you change your mind?

A: I supported the war because my experiences in East Timor, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan led me to believe that interventions could bring real benefits to the local people. I knew that Iraqis wanted rights, including the right to vote, and that they largely hated the brutality of Saddam’s regime. I believed we could give them a better life. It was the outcome that made me reconsider. If we had been able to rapidly achieve a more humane, prosperous state, with a limited cost to ourselves and to the local population—as I believe we had in Afghanistan—I would still be in favor of the intervention. Instead, tens of thousands of Iraqi lives and thousands of Coalition lives have been lost, and hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent to produce a situation that is still, three years later, fractured, dangerous for everyone involved, and often brutal and destabilizing for the region. That is what made me change my mind.

Q: What went wrong with the Coalition’s attempt to build democracy in Iraq? Could we have done it better?

A: We made many mistakes, but in the end, having seen Iraq up close, I think the intervention was always going to create a mess. Better planning and better tactical decisions might have improved things slightly, but they were never going to make us successful. The two fundamental problems were the political culture of Iraqi coalitions and the nature of Iraqi society. Neither the military nor civilian coalition bodies were very effective at post-conflict reconstruction; this was partly because the military was focused on winning battles, the foreign service officers were focused on diplomatic negotiations, and the development people were focused on alleviating poverty. None of them had the skills or the stomach for the uncomfortable politics and compromises involved in reconstructing a traumatized Islamic state.

Nor, in Iraq, did they encounter a forgiving and cooperative local population that was prepared to take a generous view of their failings. Fifty years of nationalism and anti-colonial propaganda, spiced with radical Islamic ideologies, left Iraqis very suspicious of foreign intervention. If the electricity did not work, people immediately assumed that it was a deliberate conspiracy to humiliate the Iraqi people, rather than simply a result of the Coalition’s incompetence. Iraqi society had also been hollowed out by Saddam—all power lay in the center and all security was enforced by his brutal secret services. The Coalition was forced to abolish those services in order to dissociate itself from the worst atrocities of Saddam’s regime, but neither the police nor the army could fill the void. Simultaneously, criminal forces, conservative tribal forces, and religious forces—often newly arrived from Iran—were flourishing, and there were few liberal figures at a local level prepared to take political power and fight against them.

Our errors were many. We probably should have stopped the looting, not abolished the army or the Baath party, or held elections much sooner—but even if we had gotten these things right, the situation would not have been much better. The best thing, I think, in retrospect, would have been to empower local political leaders much more quickly rather than struggling through our own very limited institutions to forge Iraq in the Coalition’s own image.

Q: How well did the civilian authority and the military function as partners in Iraq during the time that you were there?

A: At an individual level, military and civilian personnel were often helpful. But they have very different trainings, methods, and objectives. The military was often disappointed by what they perceived as civilian’s muddled thinking, political correctness, and inaction, and they were often forced to do jobs in economic reconstruction or politics that should have been done by civilians. The civilians were often impressed by the energy of the military but preferred a more cautious, bureaucratic approach. Neither group was comfortable with the skills, methods, or objectives required in my role, which were closer to those of a Chicago ward politician.

Q: Is there a more constructive model for the Coalition’s response to perceived threats to our security or to rulers we consider as despots and tyrants? When is it appropriate for us to intervene?

A: I believe that it is morally justified to invade another country and topple a tyrant. But the three real tests of intervention are pragmatic: Will the intervention benefit the people on the ground? Will it benefit the country that is doing the invading? And, is intervention actually possible? The lesson of Iraq is that invasions are intrinsically chaotic, bloody, and uncertain—it is almost impossible to predict the consequences of toppling a leader and turning society on its head. We should, therefore, set the bar for intervention much higher and be much more prudent. We should only intervene in cases of direct and terrible threat to our national interests or extreme humanitarian catastrophe, such as the Rwanda genocide, and in cases where either we are confident that the intervention will work or we prefer the consequences of failure to the consequences of not interceding.

Q: At this point, what hope is there of achieving democracy in Iraq, or even of stabilizing the country? How—and for how long—should the Coalition be involved?

A: The best hope of stabilizing Iraq lies with the Iraqi politicians, who are much cannier and more flexible than we acknowledge, and of course have a much better understanding of the limits and possibilities of local politics than any foreigner has. Shia and Sunni Arabs in Iraq have a strong sense of Iraqi national identity that they can use to avoid civil war. The Coalition’s continued presence in Iraq deters politicians from making the necessary compromises with their opponents, since they rely on us to bail them out. Despite our best intentions, the Coalition often interferes in politics because we do not approve of a candidate’s human rights record or attitude toward us. We invaded talking about democracy; we should, therefore, respect the results of elections, empower local politicians, and allow them to make compromises. This will probably create an Iraq that is more Islamist, less humane, and less progressive than the Coalition would like, but it is the best chance we have. I don’t believe that our presence is improving the situation. There is very little that the Coalition is achieving or is able to achieve in Iraq—and we need to empower Iraqi politicians to discover the solutions that we have failed to find.