Article first published on Politics Home by Paul Waugh on 6 November 2014.

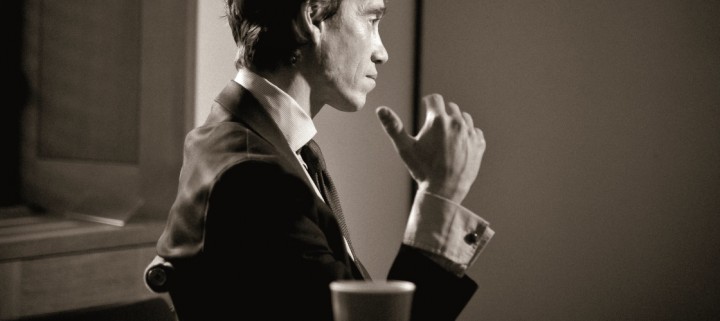

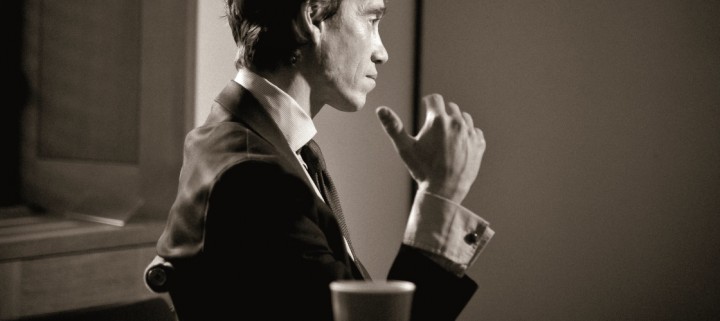

He has, famously, been a deputy governor of an Iraqi province, an adviser to the Obama administration and part-time tutor to Princes William and Harry. He walked thousands of miles across Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran, worked with the UN in Bosnia and East Timor and taught at Harvard.

Rory Stewart’s career was deemed so colourful that Brad Pitt’s movie company was keen on making a film of the life of this latter-day TE Lawrence. But no longer.

“I think it’s not on now,” Stewart reveals. “They paid me for an option, but I think they are not going to make it.” And the reason? “I think being a Tory MP is not a very sexy end to a movie,” he smiles.

Now more Stewart of North Cumbria than Lawrence of Arabia, the MP for Penrith and the Borders is these days as happy to be focused on rural broadband as he is on the Middle East.

Yet although he may be seen by moviemakers as a ‘mere’ backbench MP, the new chairman of the Defence Select Committee is still as fascinated by the global as the local.

And with its latest inquiry titled ‘The Situation in Iraq and Syria and the threat posed by Islamic State in Iraq and The Levant (ISIL)”, no one can accuse him of not looking at the big picture.

While stressing that he can’t pre-empt the committee’s report, Stewart backs limited air strikes but is wary of US promises to ‘destroy’ ISIL. “The separate question is what do you do about these guys in the long run. And then you have to do about a hundred things. That’s why people get a bit frustrated with these kind of answers, they want one answer.”

Among the solutions are using local knowledge to find and fund specific tribal groups and fighters who will provide boots on the ground. Memories of his recent trip to northern Iraq, when he visited the front line, are still fresh.

“One of the most striking things when I was there was when I asked Yezidi refugees what happened. They said ‘Well, we never saw any foreign fighters. The people who took over our village and who kicked us out were our neighbours. And the guy who is now the emir or prince of Islamic State in my town was the local manager of the electricity depot, who we’ve known for 20 years. He’s just rebranded himself as the Islamic State’.

“So as long as there is a core of support for the Islamic State among the Sunni

Arab population, you’ve got to flip those people around and flipping them around isn’t the same thing in every place.”

But among the ‘hundred things’ that can be done is a wider diplomatic push with Turkey and Iran. On Iran in particular, he says ‘you’ve got to get the relationship right’.

“There’s a man called Qasem Soleimani who is sitting in Baghdad in the way that Ambassador Bremer sat in Baghdad for the Americans in 2003/4/5. He’s running everything, he’s got weapons, he’s got troops, he’s the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, he’s like a super-ambassador to Baghdad.

“Somebody’s got to get that balance right because if those guys push too hard in the Sunni areas then the Sunni guys are going to say ‘wait a second this is an Iranian Shia conspiracy to occupy our lands’. So this is something that cannot be done without passion, energy, without drive. What worries me is if people start looking for a silver bullet or a simple solution or thinking that it can be done by deploying huge numbers of [Western] troops on the ground.”

Simple solutions could be the problem too with the forthcoming Iraq Inquiry report from the Chilcot Committee, Stewart fears. “I’m worried that the fundamental problem in the Chilcot Inquiry is that it will firstly focus overwhelmingly on the legal case,” he says, “And secondly it will imply that it all would have gone fine if we’d just done a few things differently, in other words if we hadn’t abolished the Iraqi army, if we hadn’t de-Baathified in the early days.

“I think that that’s dangerous because that leads people to believe that provided you have the right justification and provided you have a cunning post war plan, everything is going to be fine. My experience in Iraq is that the problems were so deep even in the relatively more promising Shia areas of the south that it wasn’t going to work -regardless of whether you’d kept the Iraqi army and regardless of whether you’d kept the Baath party. Doing those things would have created problems in the Shia south almost equal to the kinds of problems you created in the Sunni areas by getting rid of those institutions.”

Again, he draws on his personal experience in the region. “I had demonstrations day after day, hundreds and sometimes thousands of people, outside my office with banners demanding more de-Baathification – at exactly the time when Sunni groups were saying that the very mild de-Baathification that had begun was so completely offensive that that was the reason for their insurgency.”

In Afghanistan too, Western politicians are in danger of learning the wrong lessons from a protracted conflict, he adds. US journalist Anand Gopal’s new study of the Afghan war, reviewed by Stewart for the New York Review of Books, provides a stark contrast to a recent scorecard published by The Times in London.

“[The Times] said there are seven more million children in school. The Gopal book shows that these boasts about education are false, that in the provinces which they’ve managed to study…85% of the schools do not exist, 3,200 teachers are receiving salaries and not going anywhere near a school and don’t have any qualifications.

“The next thing they have on their scorecard is Afghanistan has a trillion dollars of mineral wealth, but again they’ve been saying this for the last six years. The reality is that with the exception of one Chinese copper mine which actually has decided not to start extracting copper yet, there is no investment in mining in Afghanistan, nor is there likely to be in the short term.

“Again they say great improvements in security, they don’t mention that more Afghan police and soldiers have been killed in the last six months than at any period since the start of the intervention.”

For Stewart, long a sceptic about Western intervention, there is one main conclusion to draw from the years of blood and treasure spent in the Middle East. “The lesson of Iraq and Afghanistan is that the idea of nation building under fire, this idea you can go and build a state and run a counter-insurgency campaign at the same time, is I’m afraid wrong. I can’t think of any historical example where it’s worked and I think history will judge that quite harshly.”

The final British withdrawal from Afghanistan took on a tangible form recently when the Union flag was lowered in Camp Bastion, Helmand. And with Remembrance Sunday this week, many inside and outside Westminster will reflect on the lives lost. But what does Stewart make of those who say that their sacrifice has not been in vain, that even the limited progress in Afghanistan has been worth it?

“It’s always very tempting, particularly in tragic situations where lots of people have lost their lives, to try to misrepresent the facts. But the reality is that every soldier’s life is valuable intrinsically and should be honoured as the sacrifice of a soldier for their country.

“The fundamental obligation that we have is, without being too pompous about it, to the truth. Because in the long run being honest about things is the only way that you can actually create policies, proper strategies to keep the country safe.”

And there’s a wider point that Stewart, who served briefly in the Black Watch as an infantry officer, wants to make. “The value of a soldier’s life should never, ever, ever be reduced to whether or not the particular battle they are fighting in does or does not achieve the objective set out by politicians. Those are not the metrics,” he says.

“A soldier’s life is something very difficult for contemporary societies to understand. It’s something that we may have been more comfortable talking about a hundred years ago or two hundred years ago. That war and sacrifice is something that a soldier joins to do and they are fighting and dying for many things. For their own unit, also for Queen and country, also for an idea of themselves.

“These things should be praised and valued and I think it’s really dangerous to start saying ‘Well was a soldier who was killed in the Somme less worthwhile than one that was killed in Aden? Less worthwhile than one that was killed in Iraq or less worthwhile than one killed in Afghanistan?’ Every one of those individual acts of sacrifice is valuable in and of itself, regardless of the surrounding local context.”

Stewart has been doing his bit to change the local context in Kabul. Seven years ago he founded a charity the Turquoise Mountain Foundation, which now employs 450 people. It cleared 15,000 trucks of rubbish from the surrounding slum, set up a family health centre and now has a primary school too. At first no girls came to the school, but after five months the charity worked out what was wrong. “We worked out that we needed to have their fathers sitting in the back row and they were happy for their girls to go to school. Now we have 50% boys and 50% girls in the school. This is trial and error, trust, deep, deep local absorption, it’s not something that can be done with a Powerpoint presentation.”

Alliance building is something Stewart has brought to his Commons career too, it seems. This summer, he surprised some by beating off more experienced contenders for the Tory chairmanship of the committee. Faced with seven rivals, he eventually pipped Julian Lewis to the post after winning the backing of a serious chunk of Labour as well as his own MPs.

“It’s a huge privilege to work with such a dedicated and experienced committee. From Colonel Bob Stewart – with over twenty years experience and a DSO to Dai Havard, who puts so much energy and understanding into the committee work – everyone on the committee is deeply serious about Defence and brings a great deal to the subject. And we’re very lucky that Julian Lewis and Richard Benyon have just decided to join the committee as well.”

But looking back since his arrival in 2010, what does he now make of Parliamentary life? “It’s quite a wonderful world, but it’s completely unlike anything that I imagined before I came in. The bits I thought would be really good turned out to be disappointing, the bits I thought would be disappointing turned out to be really good. And the fulfilments and satisfactions are very strange.”

One example is just what happens in the chamber itself. “I assumed the centre of the whole thing would be speeches in the House of Commons. And I used to be quite good at making speeches so I thought oh well it’ll be fine. But of course it turns out that whereas in the 19th century of Gladstone and Disraeli their speeches packed the House, the journalists were all there, they were reported on the front page of the Times, the whole public debate of the nation was created through speeches in the House of Commons…that isn’t true any more.

“I turned up and I found out of course what we all know. Which is some debates are pretty sparsely attended, some of us are on our Blackberries, especially when people are reading speeches. It’s not I think that people couldn’t make really good 19th century speeches, I don’t think there’s anything different really, in many ways Members of Parliament today are much more educated, more articulate than they were in the 19th century, it just matters less.

“The 19th century people would put three or four days into writing their speech, now you would be a lunatic to do that really because there aren’t enough people listening.”

But what has impressed him has been the close ties to his constituency. “Constituencies have become much more interesting, a much more engaging part of your life than it would have been in the 19th century.”

The unique location of his constituency allowed him a significant role in the Scottish independence referendum, a campaign he clearly relished. He’s also been able to make a difference on rural broadband, pushing the Government into committing to 98% coverage of the country.

“I feel I have a real opportunity in Cumbria to shape things: rural broadband, neighbourhood planning, more affordable housing. Being an MP is a perfect way of connecting with community groups. I can reach out to the charitable sector, I can raise money.

“All you can really say to yourself in terms of this idea of making a difference is that you were one pebble dropped into the water. You can be pretty sure that on its own these things don’t change things but you just hope that somehow cumulatively you are one of the things that shifts it.”

Some in the military believe that Stewart certainly had a big impact on David Cameron’s policy of withdrawal from Afghanistan. Back in 2010, he and other MPs with military and foreign affairs experience gathered at Chequers to share their thoughts with the PM. Stewart argued strongly across the table for a deadline for pull-out rather than the ‘conditions-based’ approach favoured by Gen Sir David Richards and others. Just like Obama, Cameron went for a deadline. How did it feel to win that argument on such a hugely important policy?

Again, Stewart is modest about his role. “That’s right, I said that and that was the policy. But you become aware that it’s very difficult to be sure that you saying it is why it ended up like that. I think the first thing is you realise, or at least I’m beginning to realise, just how small a cog you are in the wheel.” “

So would he say that his career to date has been an attempt to speak truth to power, rather than to wield power. Or has it been a bit of both?

“I think that’s a really difficult question. I’m a politician. And I’m not always proud of myself. There’s a lot of spin and PR to do with our lives so it’s a matter of degree in democratic politics. I think everybody in politics or almost everybody is committed to trying to be honest with themselves about what’s wrong with the country and what they’d like to improve. It’s just a question of the way in which the structures do or do not allow you take risks and how far you can push that.

“So, being a politician is a perpetual learning experience, an experiment in working how far you can push it, how much risk you can take. And I’m a new politician, I’ve only been here four years so I haven’t been I’m still probably a bit naïve, I’m still interested in trying to push those boundaries. Occasionally you push a boundary and then you realise ‘oh god, I probably went too far there, I probably haven’t been careful.’

“So one of the dangers of being a politician is you end up being very polite. So a clear example: if somebody had asked me five years ago was the surge in Afghanistan a failure, the answer would have been Yes. Now the temptation is to say ‘if the objectives were defined as the creation of a credible, effective and legitimate Afghan state and the defeat of the Taliban, then we did not succeed in achieving those objectives’.

“And it’s because you learn over time unfortunately, and it’s a sad thing, you learn that if things are taken out of context then immediately you have somebody goes and grabs someone on the street and says ‘this guy says the Afghan war was a failure, your son was killed in Afghanistan what do you think about him?’ And then whose sympathy is with some crazy politician in Westminster or somebody who’s been bereaved?’

“I suppose the difference between them [the two statements] is one is more shocking and blunt than the other and it’s to do with what you are trying to achieve in the public consciousness. In other words what is it you want people to feel when they are making a decision like that in 10 years time? When they are about to do something similar somewhere else, do you want them to have absorbed the basic thing, which is it didn’t work? Or do you want them to specify counter insurgency and state building didn’t work, which is a more precise way of putting it. And is the danger of doing that that’s so complicated that the big picture is lost: ‘Oh well there were some things that didn’t work but basically it was fine’?

“So sometimes we have to be pretty blunt and broad brush and not very academically precise in order to get the point across. In the end, politics is quite binary. Is it a good thing, is it a bad thing? Did it work? Didn’t it? Will you or won’t you? One of the things that worries me a bit is because of the kind of ‘gotcha’ culture it’s very tempting to become so polite and subtle in your statements that it’s not really clear what you are trying to say.

“So what am I really trying to say? What I’m really trying to say is the decision to send more troops to Afghanistan was a mistake, we shouldn’t have done it. and presented with the same situation in the future we should not do it. The initial intervention worked, the surge didn’t. But working out how one does that and remain alive in modern politics is quite difficult.”

Stewart certainly said what he thought when he worked with Richard Holbrooke, Obama’s special representative in Afghanistan. He argued his case on the opposite side of the table to big figures like Generals David Petraeus and Stanley McCrystal and even ended up testifying to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

“I was very, very much more involved in the American debate because I was in the United States at the beginning of the Obama administration and I was quite close to Richard Holbrooke and I would meet Hillary Clinton and I would work on stuff there. The American system is actually much more transparent, it’s much easier to know where you are in the debate and what different people’s positions are. Who you are arguing against, where the camps are.

“So in the American system I could ally myself with Holbrooke or to some extent with Joe Biden and I could see on the other side of the table was David Petraeus and Stanley McCrystal, the generals pushing the surge. In the British system, from the perception of a backbench MP it’s a very, very opaque thing how the decisions are made, where the decisions are, how many people agree with you, how many disagree with you.”

Now that he’s part of that ‘British system’, does he see himself staying in Parliament for another 10 or 15 years? “I really don’t know at all. I’m actually finding it more satisfying as time goes on,” he replies.

“If you’d asked me that question at the end of my second year, I [would have said] I was just beginning to realise how, in many ways, being a backbench MP is a pretty peculiar and potentially frustrating life. And how a lot of the consolations which were offered for that were probably not as satisfying as you might think. Now I’m beginning to see that actually one of the things that an MP can do is to get involved in a public conversation about defining what Britain is. And that’s a fascinating possibility for an MP.”

That conversation became very real this summer during the Scots independence referendum. Stewart had the idea of creating a ‘Hands Across The Border’ cairn in his constituency to symbolise the solidarity between the English and Scots.

“You dump yourself in a field, you put out the call for people to come. You sit there for the first few days getting a bit worried because nobody’s turning up, then gradually you see people from Cornwall, Argyll, Skye etcetera carrying these rocks. And we end up with 130,000 rocks so the thing is a big monument and in doing so you are connecting to the Scottish referendum debate in unusual ways.

“I realised that I’m not making speeches in the House of Common, which I did do about Scotland but didn’t have much impact, but other things did. Building the cairn did, maybe campaigning in Glasgow did, I did a BBC documentary, articles, a little bit of social media and you suddenly realise that being an MP, there are opportunities there.

“I really felt that the referendum campaign probably of all the things that I’ve done [as an MP] was the most exciting and satisfying. There was a once in 300 years decision, something I deeply cared about, my constituency was perfectly located to get involved.

“Again as with all these other things you do, you have absolutely no idea of the difference you make, whether you even added five votes to the whole thing but at least you know what you are about. And it’s really fun intellectually because you have the opportunity to take the Scottish National party and deconstruct their arguments.”

And on foreign policy too, he’s been able to use his time as an MP to improve the public debate, he says.

“On Iraq and Syria, for somebody like me who’s deeply deeply interested in British defence policy to be able to say well what are the objectives here? What are you trying to do, who are you targeting? And ok you’re targeting the Islamic State, here are your panoply of options: air strikes, boots on the ground, regional solution, political internal solution and maybe in addition attacking Syria, what are the justifications of these, what are the pros what are the cons and where does Britain fit into this? There’s this big monster called the United States, we are a small country we have a few planes, what are we doing?

“These things I don’t think I could do anywhere else. Or at least if I were to do them somewhere else I would be in the frustrating position of testifying to a committee as opposed to being the questioner.”

Now Stewart is the one doing the questioning as the Defence Select Committee oversees various inquiries. But although his own days as an expert witness are over, he hasn’t ruled out another role: becoming a minister one day.

“I think a dream career would also involve, at some point in my life, looking at it from the other side. It’s quite difficult to scrutinise the government if you don’t have any idea what the inside of the machine looks like. And that was the advantage that James Arbuthnot had, he had been a defence minister so he had an idea what was a realistic expectation to set on these poor guys sitting across the table from him.”

There are other attractions too. “I also think there are certain things I would love to do which you could probably only do by being a minister. For example, I would really, really love to focus on developing area expertise in the military, to see the military go into a much deeper form of defence engagement,” he says.

As an example, Stewart says the UK could learn a lot from copying the French system of expert defence attachés.

“Our defence attaches tend to be people at the end of their careers doing a two year posting before they retire. The French defence attaché in Tripoli on the other hand was taught Arabic for two years, went to the Egyptian staff college, was the defence attaché in the UAE for three years, was the defence attaché in Egypt for two years and is now in Tripoli.

“It’s completely different and when you see the French success intervening in Mali that’s all about that structure of defence engagement there. The reason the French can arrive in 96 hours and deploy is that their defence engagement is so deep and intimate that they have the platform to allow that to happen, which we don’t have in Britain.”

“Now if I wanted to do that I can’t do that as a backbench MP. I actually have to get into the nitty gritty of the essentially the HR personnel structures of the military, work out how they people are recruited, how they are promoted, what kind of language allowances they receive, how their career structures work, how you attach a brigade to a particular area.”

Speaking of defence attachés, that title was often a cover for British spies in the past. Some have hinted that Stewart himself was a spook. So, was he ever in MI6, and if he was would he ever reveal it? He laughs. “The answer to the latter question is absolutely not. The answer to the prior question is No.”

Confirmation that he never was a James Bond may be one more reason for Brad Pitt to resist that film option. But Stewart has at least given the movie of his life a romantic storyline, having two years ago married Shoshana Clark, an American aid worker who worked with his charity in Kabul.

What’s more his wife is expecting to give birth to their first child as The House goes to press. Stewart upset a few parents when he last year told the Radio Times that children were ‘the opium of the masses’ and that some people felt their purpose in life was their offspring. Now that fatherhood looms, does he think differently? Again he smiles. “I may well end up eating my words…”

‘Rory goes to Hollywood’ may not be the next headline that attaches itself to the MP for Penrith and the Borders. But with new family adventure and a possible ministerial future ahead, his colourful career isn’t over yet.

RORY ON…BREXIT

“I’m absolutely in favour of the idea of a referendum. I do think this is fundamental to Britain. The British public tend to make the right decisions on things, I think the British public have made the right decision in every election since about 1900, I don’t think they’ve ever got it wrong. And they’ve just made the right decision about Scotland so I have full confidence in that. I also think you can’t keep pushing it under the carpet.

“I suppose I feel what I really would like to do over the next two years is make sure people understand what it is they are voting for. In other words almost more important than a lot of people who are going to go out campaigning for one side or another, I just believe there’s a huge job in explaining what the risks and benefits are of the choice on both sides so people are open eyed. It’s perfectly respectable I think to vote both ways provided you understand exactly what’s involved in that choice. That’s what I think is missing in this debate.”

But is his gut feeling we should be in or out?

“My gut is that if the British people are really up for risk for a period of instability if they are prepared to take the risks that there could be a period of serious economic adjustment and they want to embark on a grand heroic independent task then they should be allowed to do that.

“But they need to understand that that is one of the risks they are taking, it’s not going to be easy all the way. And the question for the British public is two years after the vote, if the economy is struggling a bit and there’s a nasty divorce going on and Europe isn’t being as cooperative as we’d like, are people still going to feel it’s fine, I don’t mind suffering because in the medium to the long term we are going to be this different, independent country. Or are people really not up for that in which case they should really vote the other way.”

“I love the idea of buccaneering but the point is this is a decision the British public’s got to make, not me. I might prefer to take more risk and be more buccaneering, the British public has got to work out what they are up for.”

RORY ON…MISSING THE SYRIA VOTE IN 2013

Referring to the fact that he was at his sister’s wedding in Devon on the day:

“It’s slightly farcical. When they [the whips] realised that they needed the vote, I got a text in Devon. I arrived about six minutes after the vote having missed the wedding dinner. The worst of all worlds.”

RORY ON…AFGHAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS

“The position of women in Afghanistan is improving all the time. They’ve never been so educated, they’ve never had such exposure to public life. If I look at the women who work in our organisation they are pretty tough I can’t see that they are going to be pushed aside very easily but it is difficult, you are relying on cultural change. We still have honour killings happening in Germany and Britain.”

RORY ON…’GOOD INTERVENTIONS’

“We got things really right in interventions in Bosnia and to some extent in Kosovo. If we just focus on Bosnia, that really was a miracle. There were a lot of people saying in the early 1990s this is impossible, stay out, centuries of ethnic hatred, these guys are lunatics, we don’t understand it, none of it will do any good.

“And we went into a situation which 150,000 people had been killed, 130,000 people armed, war criminals on the loose a million people being kicked out of their houses. And by intervening we ended up with a situation in which a million properties have been returned to their owners, in which checkpoints have disappeared, in which every single war criminal has either died or been captured and put on trial. In which the militia groups have been demobilised to a security force of about 5,000 people and the crime rate is now lower than Sweden. And all that without any British or American troops being killed.

“That is a good intervention. People who say all interventions are bad, should look hard at Bosnia. They could also look at Sierra Leone, they could look at the Australian intervention in East Timor and the Solomon Islands and they could probably look at the early intervention in Afghanistan, from 2001 to 2003.

“In Bosnia, we were slow to intervene but that was probably in retrospect also a good thing. It meant that by the time we went in it was clear the reason we were going in was humanitarian, we were going in reluctantly. One of the reasons why we didn’t have more problems in Bosnia – more Americans were injured on the basketball pitch in Sarajevo than were injured in the whole conflict – was because at the moment we went in, essentially a regional solution was emerging where Milosevic and Karadic had decided to back off on the Serbian side. And Tudjman had backed off on the Croatian side. The European Union was a very important part of that.

“I think initial stage of the involvement in Bosnia was very, very difficult, there was the shame of Srebrenica and the inability to defend that, but again it’s a very, very difficult to say much more than in the end Bosnia worked. Of course many people assume that had we gone in earlier we would have been able to make it work earlier.. I think that’s unproven. At the point we went in the Bosnian Serbs were losing territory. Holbrooke comes in at the time when the Bosnian Serbs were on the back foot and are ready to make concessions. If we’d tried to go in in ‘93 there wouldn’t have been any components of a peace settlement.”